Our next full BCarbon stakeholder meeting will be on Thursday, September 8th, at 9 AM CT. In this call we will propose that Principle 12, on the importance of ecology to the BCarbon system, be added to our soil carbon principles. This principle reads as follows:

“Overall ecological integrity is a higher priority than transacting carbon credits on a standalone basis.”

As always, feel free to reach out to Jim (jim.blackburn@bcarbon.org) or Robin (robin.rather@bcarbon.org) if you would like to talk one-on-one with the BCarbon team!

In the July issue of The Atlantic, Julia Rosen makes a compelling argument in the article Trees Are Overrated that grasslands have been overlooked, if not discriminated against, by the international carbon credit market. Forests are dominant in the realm of nature-based carbon credits, as that they represent well over 90% of nature-based carbon credits.

Forests are certainly important to carbon removal, but their ability to help us address the build up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is far from unique. Indeed, BCarbon was formed with the goal of bringing grassland carbon credits to the voluntary carbon market, and we are just beginning to make it happen.

Figure 1 displays the major prairie ecosystems of North America. As shown, the tallgrass prairie system extends from Texas to Canada and east to the Mississippi, the mixed prairie stretches well into Canada from Texas, and the shortgrass prairie covers the western part of the Great Plains adjacent to the Rocky Mountains. Also shown are the Western Gulf grasslands of Texas and Louisiana, the Palouse grasslands of Washington, Oregon and Idaho, the Basin Steppe, and the grasslands of the California Central Valley.

Grasslands are both overlooked and endangered. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the prairie ecosystems of North America are some of the most severely endangered biomes on the planet. These ecosystems are threatened with conversion to croplands, overgrazing, and poor livestock management. Only 1% of Texas’s prairies can be found intact today.

Conversion of prairies to cropland could result in the release of upwards of 30% or more of the carbon stored in the soils of these ecosystems. Similarly, overgrazing disrupts the ecological wellbeing of prairie grasses which can lead to the loss of soil carbon. Taken together, these processes are devastating for soil carbon sequestration, as well as for the habitat value these prairies hold for grassland birds and pollinators.

As can be seen from the map in Figure 2, significant portions of the grasslands of the Great Plains have already been converted to cropland with more being converted every year. Of the approximately 624 million acres of Great Plains grasslands originally in the United States and Canada, around 40% have been converted to cropland as of 2019, with an additional 2 million acres being converted every year. When overgrazing is considered as well, the results have been catastrophic for natural grasslands.

As a result of conversion and degradation, populations of grassland birds and pollinators have significantly declined. Today the lesser prairie chicken is on the brink of extinction, and recently the monarch butterfly was listed as an endangered species. Grassland birds have declined at a higher rate than other species, with around a 40% drop in population since the 1960s according to the National Audubon Society (NAS).

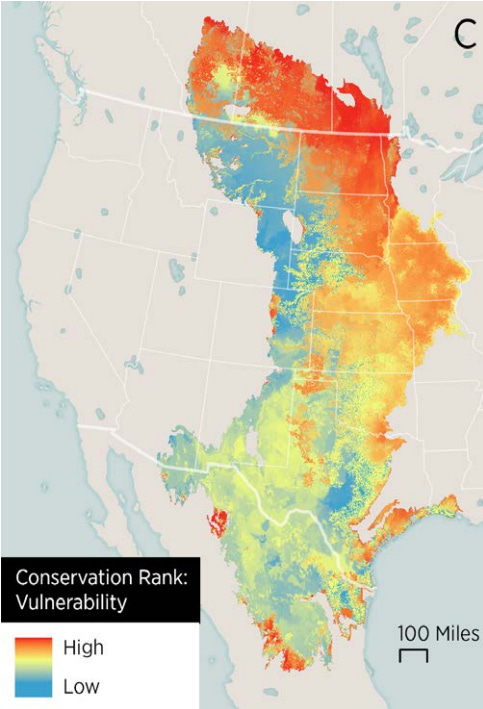

NAS has created a map of vulnerable regions of the Great Plains, which is shown in Figure 3. The vulnerability of these lands is based on several factors. Land conversion is the greatest risk on the eastern side of the map, where tallgrass prairies have been heavily impacted by conversion to cropland due to their excellent soils and relatively dependable amount of rainfall.

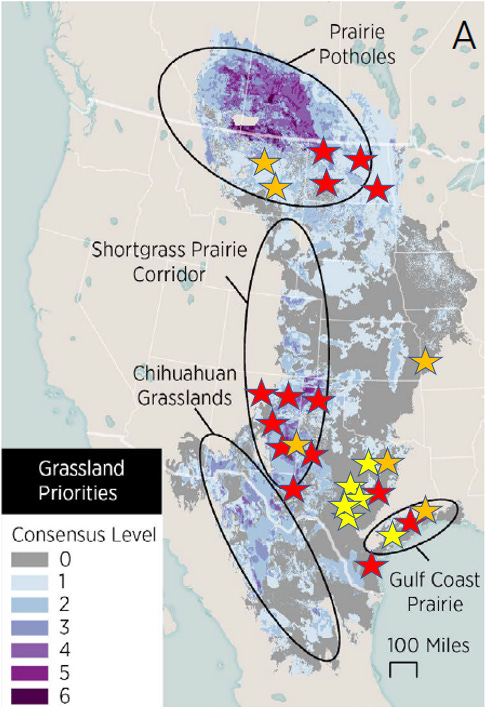

In their analysis of prairie habitats, NAS also identified high priority areas for conservation. As shown in Figure 4, areas were selected based both on the potential risk of climate change as well as the opportunities for longer-term conservation. Coming out of this are four high-priority conservation regions — the Prairie Pothole region of Canada and the U.S., the shortgrass prairie corridor running along the western side of the Great Plains, the Chihuahuan grasslands of west Texas and northern Mexico, and the Texas Gulf Coast grasslands area.

Right from the beginning, the BCarbon’s has been to open the carbon credit market to rangeland stewards. In 2021, only two soil carbon projects were initiated by registries using the Clean Development Mechanism. There is no way that we can reach the scale of carbon removal necessary to effectively combat climate change at this rate, nor will this pace satisfy the long-term conservation needs of prairie grassland ecosystems. For this reason, BCarbon created a carbon crediting mechanism outside the boundaries of the traditional approach.

To implement this system, BCarbon has catalyzed innovative research in prairie grassland ecosystems. With funding from ExxonMobil, BCarbon has begun soil carbon testing in the various prairie grassland systems of the United States. Six private property test sites have been identified in Texas, and four test sites have been identified in North Dakota and New Mexico in collaboration with their respective state governments. As can be seen in Figure 5, the test sites selected for the ExxonMobil research map onto the conservation priorities of the National Audubon Society, offering both carbon and conservation benefits for what BCarbon is calling their Prairie Carbon Strategy.

In addition to the tracts shown in Figure 5, BCarbon is working on processing soil carbon applications from Florida, West Virginia, Washington, and Oregon, as well as from South America, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where BCarbon recently issued its first no-till agriculture soil carbon credits to Future Food Solutions.

Grasslands and no-till croplands have tremendous potential to sequester carbon decades into the future. According to a recent article in Nature Communications, global soil carbon stocks are currently at about 42% of their potential capacity, and with appropriate land management can accommodate around a billion tons of carbon sequestration per year in croplands alone. This is readily available, nature-based carbon removal that it would be foolish not to develop as one of our key climate solutions.

In summary, BCarbon has developed a prairie soil carbon conservation strategy that is sweeping in scale and vision. BCarbon will work with owners of grasslands and no-till croplands around the world to fulfill the potential that soil carbon holds for reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Soil carbon alone will not be the solution, but it will be a key part of the carbon reduction portfolio of the future.

Jim Blackburn, CEO and Chairman of the Board of BCarbon